Of icebergs and personality tests: measuring ourselves

Recently, I was spending a perfectly lovely weekend with my eldest. He was telling me how he and his co-workers all took a popular online personality test. “It was fascinating,” he said. “I had no idea I was like all of these famous people! And then, I took it again, and I got a different personality type!”

I winced.

“Mom – I thought you’d be excited about this,” he said, accusingly. “You use personality tests for your assessments. Shouldn’t you be happy that I took the test?”

Um. Well.

Personality is, inarguably, a core piece of our executive assessments at Ascent. We put our personality test side by side with what we call executive capabilities, so we can show not just how people work, and at what level they work, but also what drives them to do what they do. The problem is: how do you define personality?

I asked my son to define personality. He thought it over. “It’s how I express who I am. What matters to me.”

It’s a fair definition.

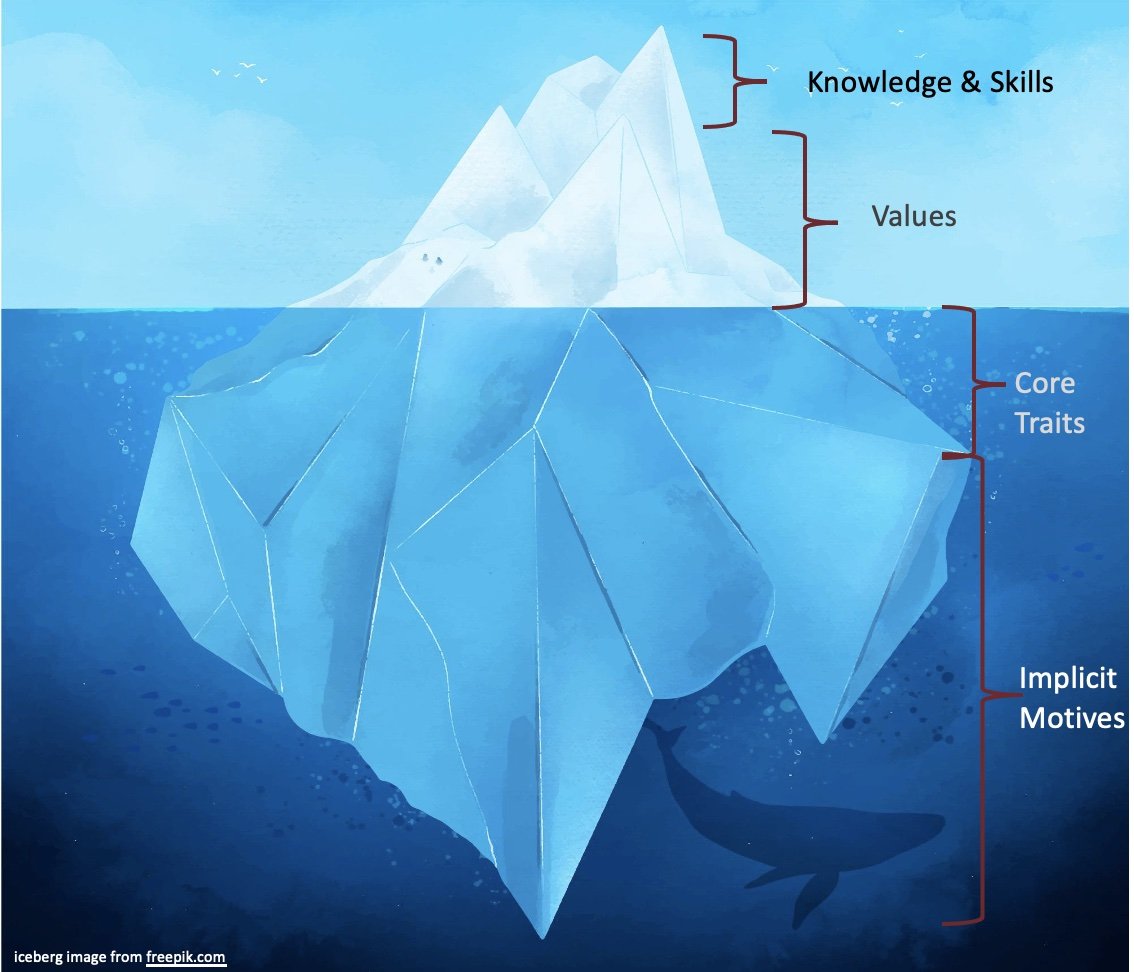

The elements of (let’s call it) “personality,” are layered, with some hidden and others clearly visible. These include:

Your knowledge and skills. This is the most visible level; it’s what you’d see described on a resume.

Your values, or how you express what matters to you through your daily actions, what you choose to say or do in a given situation.

Your deeper traits, including your capacity to understand yourself and others.

Your implicit motives, or non-conscious emotional drives. Three of these – Achievement, Affiliation and Influence - are the hidden drivers of roughly 85% of your thoughts, your choices and preferences.

Dr. Steve Kelner, motivational psychologist and Ascent’s President, points out that each level of (my admittedly simplified) personality iceberg is fueled by the one below. So your values have an impact on the situations you choose, the experiences you have, skills you choose to develop. Those values are, in turn, shaped by your core traits. And everything is fueled by your implicit motives, which shape the pattern of choices and preferences over time.[i]

For example, a person with high levels of Achievement motive is typically driven to set and surpass goals over time. If they start jogging, they may go on to a 5K, then a 10K, a half marathon, and so on. In the course of this, they’ll be leaning on their perseverance, reinforcing the value they place on self-care and fitness, and developing skills in pacing themselves, how to layer up on a wet, windy day, and so on. All driven by that deep seated Achievement motive, fuelling each layer of their personality, driving them to try to hit their next target, reach for that next challenge.

If each layer of the personality has an impact on who we are and how we function in our personal and professional lives, then the question is, what do you want to measure? And why?

People who take personality tests talk about the opportunity to understand themselves and others, and to think about why they might clash with a particular colleague. And, if all you want is an experience to highlight the value of respecting and adapting to each other’s differences, then the top layer of the iceberg works just fine. A test at that level focuses on values and behaviors – the things we see. And, what we see tends to feel significant to us.

Unfortunately, those upper layers also tend to be more fluid, or context-specific. Your values are triggered by your environment, or heightened by current events and more immediate needs. Did you just see Schindler’s List? If so, you’re more likely to choose an answer about being an upstander. Having context-sensitive responses allows us to adapt and learn from a moment and our environment. But it also means that a test that focuses on these layers – the expressed values - will be less reliable. And a test designed for mass market use is more likely to force the selection of a single choice, rather than being open to individual expression or whatever people decide to offer at that moment in time. It’s a pragmatic, if problematic design choice; simple, check box choices are more easily scored by a computer, but potentially less accurate.

***

If all I wanted to know is which Hogwarts house I’d be in, then this would be simple - assuming I remember not to take the results too seriously. As my son learned, today’s Ravenclaw can be tomorrow’s Gryffindor. But if all I’m after is a thought-provoking snapshot of myself in the moment, then that’s me sorted.

As an assessor, though, my goals are different; I want to measure something that is meaningful, reliable, and stable over time. My clients are making long term, high risk decisions, so if a test isn’t reliable, or the answers are variable, then it’s not accurate enough for me to use. So, when I include personality in an assessment, I focus on the foundations of the self - the non-conscious, implicit motives. The implicit motives are so stable that they can be identified in children, and tracked, largely unchanged as that child grows up.[ii] The values may change, or traits be expressed in increasingly sophisticated ways as a person matures, but your motives mean that you remain you.

Which leaves me with one critical challenge: finding a test that is meaningful. And meaning always depends on the reason behind the test. Our clients ask complex questions, whose answers have strategic consequences over time. For them, a meaningful test is one with results that will let them build strategy, make decisions and have the capacity to respond and adapt. That means focusing on the stable, foundational personality elements, like implicit motivation, and a projective test design that doesn’t anchor or limit what people choose to say in response. And while the toolkit we build depends on the client, their need, context and so on, we’ll often include personality tests in our assessment toolkit for asks such as:

Individual Executive Assessment: these are often used to identify if an executive has the capabilities for a given role. By adding implicit motivation to these assessments, we can address a rather critical, fundamental question: will this job, this environment be a space where this person is likely to be happy, be energized, and continue to grow? It’s a simple but important question; in our experience, people tend to choose jobs rationally, but leave because of their feelings.

Culture: whether our clients are tackling employee experience, DEI, or looking to preserve a particularly special work culture, implicit motivation is one of the first things we add to this assessment kit. Culture, according to Geert Hofstede[iii], is a collection of "systems of values,” shared by a group of people, which create “patterns of thinking and feeling, and potential acting.” Adam Grant[iv], an organizational psychologist, is blunter. Culture, he says, is “what you do when the leader isn’t watching.” It’s the sum of actions taken by individuals, and how they impact others, setting norms and shaping relationships. If I’m looking to understand that sum - the individual, behavioral and structural elements that shape a company’s culture, then implicit motivation will tell me where people tend to align, clash - and what’s most likely to fuel any needed change.

Assessment for development: it’s great to have precise, unbiased assessments of where your people are, their aspirations, the gaps that need closing, etc, but helping them close those gaps? This is an entirely different challenge. But no worries – implicit motives will map what fuels your people. Equipped with that understanding, you can use a pull for development, rather than a push, helping them go in the direction they’re already energized to go.

Assessment for succession planning: for this we’re looking 5+ years down the road, at a candidate’s potential to develop. For these high stakes, high risk decisions, I’d want my toolkit to include a test that focuses on the foundational elements, as well as mapping the current state and likely path forward. Research has shown that implicit motivation can shape the trajectory of an entire career, so implicit motives it is. [v]

I looked at my son, whose eyes had narrowed while I sat there pondering all of this.

“Um,” I said, wisely. “So, what were you hoping to get out of taking the test?”

He flung his hands up. “We were just having fun, mom. It was really interesting to see the tests show how I’m different at different moments.”

I raised an eyebrow. “Fun, eh?”

He looked at me, sidelong. “You do know what that is, don’t you?”

I grinned. “Vaguely. By the way, did I tell you that I’m a Ravenclaw?”

References:

[i] It’s worth noting that each level doesn’t determine the next level up, but it does indicate how behavior is influenced. So, motives provide a directional energy, which the traits empower, constrain, redirect, which then is filtered by your values, and so on. Motives aim and energize behavior, but don’t determine the level above them – so someone with high Influence motive can also have low EQ (trait), but a strong value around engaging positively with others, which can lead them to study microexpressions. (Steve Kelner, personal communication, 4/2022.)

[ii] David C. McClelland, Carol E. Franz. Motivational and Other Sources of Work Accomplishments in Mid-Life: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Personality, 60:4. December 1992.

[iii] Geert Hofstede, 1984 and 1991

[iv] Adam Grant (@adamgrant) 10/8/2019. https://www.instagram.com/p/B3XCJj8pgUs/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link Accessed 3/12/2022.

[v] Ruth L. Jacobs, David C. McClelland. Moving up the corporate ladder: A longitudinal study of the leadership motive pattern and managerial success in women and men. Consulting Pyschology Joural of Practice and research, 46(1), 1994. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1994-43310-001